Why is it that legislation can be so difficult to comprehend?

Clearly, anyone reading an Act of Parliament needs to be able to understand the rules being laid down, the legal terms used, how the new laws interact with existing statutes and the common law, the impact of previous judicial decisions under the Act. It’s a complicated and well-remunerated process.

But before that process can even begin, the reader needs to establish exactly which text, or which parts of the text, actually applies in any given circumstance. This isn’t a case of simply reading a text as presented; rather it’s dependent on the commencement and geographical extent of each passage of the text, or of any changes made to other texts. It’s like trying to read a dense and complex novel without being sure which paragraphs are actually part of the story.

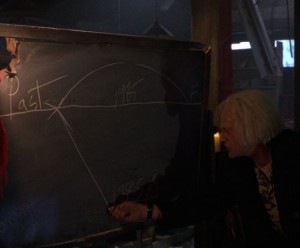

Establishing which parts of individual pieces of legislation apply where and when has been a recurring theme of my work in legal publishing over the years, and it’s helped me to think of these overlapping applications in a visual form as a matrix of timelines which, in a flight of grandiosity, I called the Unintelligibility Matrix (and which, in the absence of a better name, I’ll stick with here). It was inspired by this.

So what follows is, I hope (a) a straightforward explanation of this aspect of legislation, and (b) the basis for some thoughts on how legislation should be published and, perhaps, drafted.

The first dimension

It hardly needs explaining that enactments change over time by a process of amendment. These amendments each take effect from a date after (ok, usually after) the principal Act comes into force. On this basis we can view the life of an enactment on a one dimensional axis, ie time, on which each amendment creates a new ‘version’ (Vn) of the enactment that takes effect until the next. A series of consecutive versions from enactment through to repeal.

This is how most legal publishers have modelled legislation, and by and large it works very well. The reader has the capacity to view the text of an enactment on any date between its passing and the present.

The second dimension

But in fact it’s often a simplification. In many cases we need to introduce a second axis to properly explain how legislation changes over time. This is because the application of an amendment is often limited in some respect (usually geographically) either temporarily or permanently. The complicating factor is that we don’t know in advance what form this limited application will take, and so modelling it is difficult. We can probably call this axis ‘Application’ as a catch-all term.

Perhaps the simplest example is that of an Act which is amended in relation to, say, Scotland only thereby creating a new version (Vs) of the text for Scotland, but retaining the existing version for England and Wales. The matrix looks like this

It very obviously demonstrates that we now have two ‘live’ versions of the Act (Vs and V2), and that the one-dimensional axis can’t model the true state of the law. We’re on our way to unintelligibility.

In fact, even where we appear to have a series of neat, one dimensional changes, we often don’t. In many cases the amending legislation will (very sensibly) account for transitional cases, meaning the old version, possibly in a modified form, continues to have effect for cases decided, or in train, when the amendment takes effect.

Publishers usually try and fudge this kind of scenario to make the transition appear one-dimensional (and to fit their models). This is fine as far as it goes, but fails to fully reflect the state of the law.

In that type of example, we have the further complication of not knowing how long the old version should be treated as remaining ‘live’. And if the old version is explicitly ‘saved’ in relation to a class of persons or circumstances, that version can remain live in perpetuity.

Any two dimensional split may only be temporary. So, for example, where an enactment is brought into force in stages as part of a phased implementation, we will for the duration of the implementation have two ‘live’ versions: the version in force (in whatever place or for whatever purposes it may be) and the version not in force (for all other purposes). But, once implementation is complete, we’re back to a single axis.

To make matters even more complicated, it’s perfectly possible for an enactment to split several times over several different axes. So we might have an Act that is amended in relation to Scotland (thereby creating a new timeline) where what remains is subsequently amended in relation to England only, with each amendment having a phased implementation and associated transitional provisions and savings. This is where the Unintelligibility Matrix gets its name.

So, in essence, the matrix is just a way of modelling legislation both over time, and over its application to different people and places. There’s nothing very clever about it, but I’ve found it to be a useful way of understanding and explaining the process.

But it does lead on to some thoughts about how legislation is published. I don’t think any publisher has fully exploited the two dimensional nature of the matrix, instead preferring a utilitarian approach (which is the version with the greatest benefit for the greatest number?) or fudging the issue by trying to show all versions in one.

Which is all good and well given the cost adapting the models to what will be for some readers an irrelevance. But not for any reader whose case, or area of interest, happens to fall within a version not accounted for, or who simply wants to try and comprehend, say, the Child Support Act 1991 (an Act whose matrix is so horrendously complicated, legislation.gov.uk haven’t even yet attempted it).

And if we hope one day to be able to make more use of machine processing and understanding of legislation we will need our models to properly reflect the true state of the law. We won’t be able to fudge this issue any more.

One final thought: is there anything we can do to head off some of this complexity at the drafting stage? Well, the scope is probably pretty limited. But there are some examples of enactments that have tried to simplify the law by reducing the number of ‘live versions’ on the statute book. It understandably slipped under the radar, but LASPO actually did a rather good thing in consolidating all the scraps of saved legislation relating to the release of prisoners in a single Schedule in the Criminal Justice Act 2003. I think this approach could, within reason, be used more frequently.